People from all walks of life can take inspiration from lesser-known anecdotes, which helped create the world’s most successful company

“The most powerful person in the world is the storyteller. The storyteller sets the vision, values and agenda of an entire generation that is to come.” — Steve Jobs

Earlier this year, Apple became the first company to be valued at US$3 trillion. To put that into perspective: if Apple were a country, it would be the seventh largest economy in the world. Bigger than Italy. Over six times bigger than tech hub Israel. And almost as large as innovative India.

Had this feat been achieved by a century-old conglomerate with oodles of dynastic wealth, many of us wouldn’t have batted an eyelid. But it wasn’t — in fact, quite the opposite.

Apple was founded in a scruffy garage in the working-class suburb of Los Altos, California, by two college drop-outs with barely a dime to rub between them. Even more interesting is how Apple was formed in the dark and disillusioned late-1970s, a period marked by political and cultural conflict, and where confidence in capitalism hit rock-bottom.

Despite that, founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak sold their Volkswagen bus and Hewlett-Packard calculator respectively, to bankroll the new company with just US$2,000 combined. Given their circumstances, it was a huge financial gamble.

Success stories

The story of Apple’s founding is well documented, as are many other moments in its 46-year history. Most of these relate to the company’s meteoric rise, both financially and in terms of its global reach. However, as in all walks of life, an upward trend curve never tells the full story.

Movies have dramatised the rise, fall and comeback of Jobs, for instance, and many books describe how the Macintosh (Mac) was the first computer to talk. Yet what’s not necessarily captured in these narratives is the culture that Apple nurtured. This not only gave the company a lead against rivals — but also went on to create the iconic products and brand loyalty that made Apple so successful.

That Apple dared to be different is evident — but how that translated into success is even more intriguing.

Beyond Apple’s polished ads, interviews and corporate presentations lie a plethora of largely unknown accounts, drawn from both best-selling and lesser-read books, written by those who personally knew Apple’s original players. From these, it’s clear that while the company’s highly publicised achievements helped propel it forward, equally as important were the largely untold stories about surviving and thriving, and doing things differently — accounts that readers from all walks of life can take inspiration from.

Think big, start practical

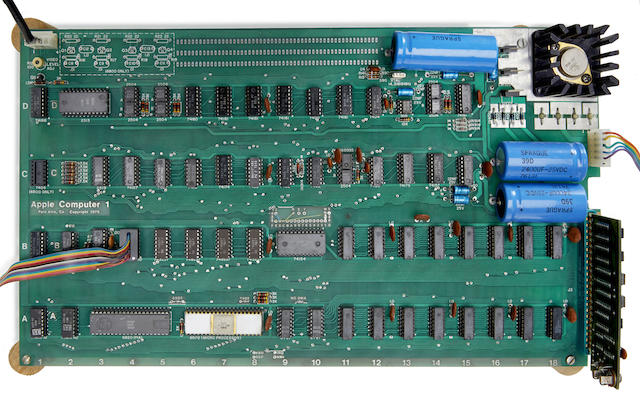

Speak to anyone who owns an Apple device, and at some point they’ll gush over how beautiful it looks and feels. The Apple I was the opposite. It was just a motherboard with no casing, no keyboard and no monitor. There were no power cables either.

Jobs and Wozniak founded the company to change the way people viewed computers. In 1976, the year Apple was formed, computers were widely seen as complicated and difficult to use. While the Apple I wasn’t explicitly viewed as revolutionary by its first customer, retailer and Byte Shop owner Paul Terrell, the fact the motherboard was sold as a fully assembled microcomputer made it far more user-friendly than rival models. Back then, owners were expected to assemble motherboards themselves by placing components inside a casing in a specific manner — similar to how we put together IKEA furniture today. ‘Why waste time building a computer?’ was the sales pitch.

This gave Apple a competitive advantage over larger, more established and better-known brands Commodore, Atari and IBM. Its relatively low price was a plus too; the units didn’t cost much to produce as Wozniak built all 200 units delivered to Terrell by hand.

Sales of Apple I helped fund the development of Apple II, which included a keyboard and case. Venture capitalist Mike Markkula’s investment of S$250,000 into Apple in 1977 was also significant; he clearly appreciated the potential of its all-in-one model. The rest is history.

Non-techie leadership

Surprisingly, none of Apple’s seven CEOs to date have come from computer science backgrounds. Unlike Google’s Larry Page and Sergey Brin, or Microsoft’s Bill Gates, no Apple leader had spent a tour-of-duty immersed in coding. Though that’s not to say they didn’t understand the computer industry. Many were trained in industrial engineering, and had worked in executive roles at other tech companies.

Performance-wise, Jobs and current head honcho Tim Cook were light years ahead of Apple’s other CEOs; yet along with former PepsiCo boss John Scully they were the least experienced in computer science.

Jobs — who as we all know was Apple’s driving force during his two stints in the company — initially studied psychology and philosophy. He later dropped out of Reed College to learn more about art, history and Zen Buddhism. Similarly, Cook graduated from college with a degree in industrial engineering, but is known for his ability to reinvigorate struggling companies by finding cost efficiencies, fixing logistics systems and closely controlling inventory.

Both produced impressive financial results during their tenures. Prior to Jobs’s first financial year in charge, Apple lost about US$1.04 billion. A year later it made US$309 million in profit. And under Cook’s leadership, Apple became the first company in the world valued at US$1 trillion.

Their success demonstrates that good leaders don’t always need to know every technical detail to be effective.

Collaborate, delegate and empower

Much has been said and written about Jobs’s controlling behaviour during his combined 22 years at Apple. Former colleagues recall him being repeatedly rude to Apple staff, as well as partners and the media. Others said he had a tendency to claim the ideas of others as his own.

“Very often when told of a new idea, he would immediately attack it and say that it was worthless or even stupid,” recollected Jeff Raskin, Apple’s former Mac lead. “But if the idea was a good one, he would soon be telling people about it as if it was his own.”

While there are many stories like that, those close to Jobs mostly lauded his ability to work closely and cooperatively with others. “His entire career was built on deep collaboration,” enthused software engineer Andy Herzfeld, one of Apple’s first employees and a member of the original Mac team. According to such accounts, not only was Jobs prepared to collaborate with people that he respected, he would publicly praise them for their ideas, even ground-breaking ones.

For example, the idea for the original Mac was Markkula’s, something Jobs never denied. Markkula is the reason we call the computer a Mac. It’s named after his favourite crunchy apple, the McIntosh — though he spelt it “Macintosh” to avoid confusion with high-fi manufacturer McIntosh Laboratories.

Likewise, the iPod was created by Jonathan Rubinstein, Apple’s former Chief Hardware Engineer, and Tony Fadell, an engineer brought into the company to specifically build the music player. While Jobs was the person who conceived the iPod, he never claimed credit for its development or design. Similarly, the concept of the iPhone was put forward by two Apple veterans: Mike Bell and Steve Sakoman. Both were convinced that computers, music players and mobile phones would soon converge. Jobs wasn’t. Frequently he would bemoan the lack of innovation at handset builders like Motorola, as well as criticize their ‘clunky’ looks. After months of lobbying, Jobs eventually gave the go-ahead for the iPhone.

Most notably, Jobs emphatically backed the work of Jony Ive, Apple’s former Chief Designer. In a career that spanned 27 years, from 1992 to 2019 Ive designed various incarnations of the iMac, iPod, iPhone and iPad. He even helped design Apple’s current corporate HQ, Apple Park, with architect Sir Norman Foster.

By empowering these people, Jobs motivated them to create products for Apple that were far superior to the competition in terms of functionality. But more than that, he cultivated in them long-term loyalty to the company.

Connect emotionally

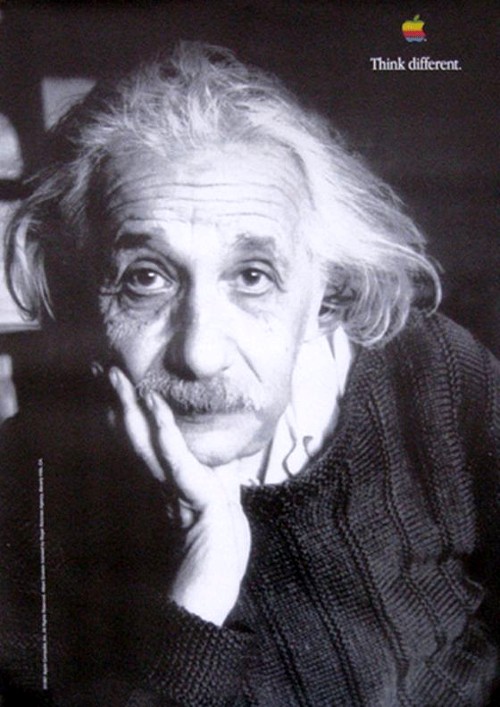

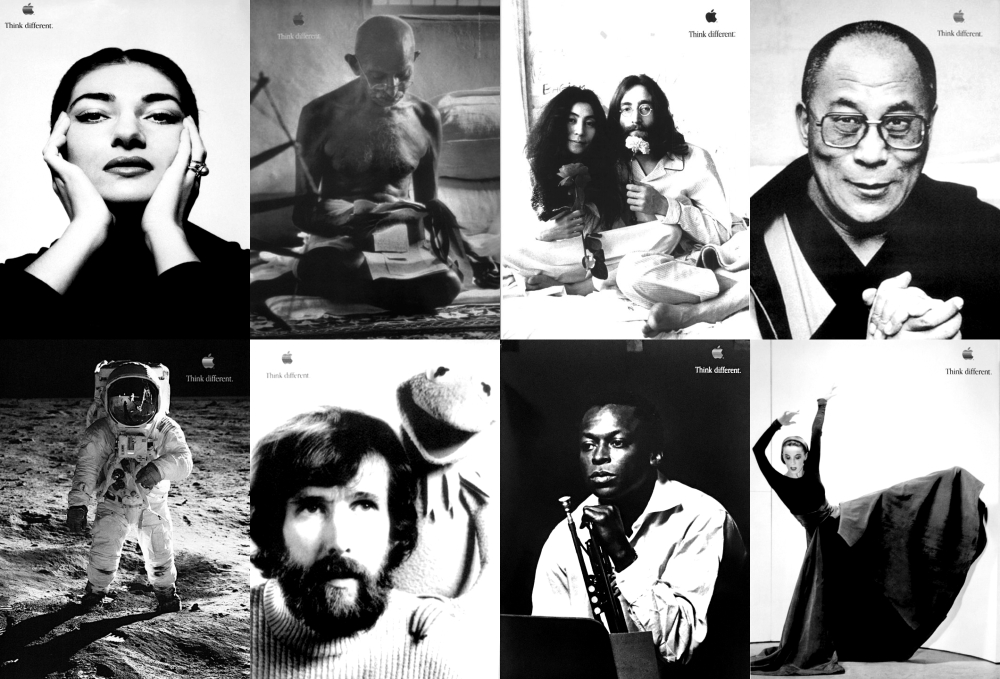

Even when others urged Jobs to take centre stage, sometimes he refused. When developing the “Think Different” ad campaign in 1997 to prepare for the launch of the new iMac the following year, Jobs chose not to feature any Apple products in its print or TV ads. He also declined to narrate the famous Here’s to the Crazy Ones ad, when prompted by its co-writer Lee Clow of ad agency TBWA\Chiat\Day.

“If we use my voice, when people find out they will say it’s about me,” Jobs asserted. “It’s not. It’s about Apple.” Richard Dreyfuss narrated the ad instead.

Apple campaigns aim to connect with the beliefs and values of customers, rather than their product needs — and Think Different epitomised this approach. Appealing to creative and disruptive individuals, the campaign’s print ads featured innovators who changed the world: Einstein, Gandhi, Picasso, Boy Dylan, the Dalai Lama, and several others.

Each ad featured a black and white portrait of one individual, with an Apple logo and the campaign’s strapline.

Similarly, the Here’s to the Crazy Ones TV ad was shot in black and white featuring these individuals to Dreyfuss’s narration:

“Here’s to the crazy ones: the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently — they’re not fond of rules.

“You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them, but the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things.

“They push the human race forward, and while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the ones who are crazy enough to think that they can change the world, are the ones who do.”

Apple connected with people’s aspirations like no other brand. Consider Apple’s 1984 ad, which appealed to consumers’ distrust of large Orwellian organisations. It set the stage for Apple to pitch computers as a celebration of what creative people could do with these devices — rather than a celebration of the vast array of tasks a computer could do.

The same can be said for the iPod. While the likes of Sony and other music player manufacturers focused their marketing on glossy images of their respective devices, for the iPod, Apple featured a silhouette of a dancing person, with the strapline “1,000 songs in your pocket”.

Inspiration from anywhere

Since day one, Apple under the leadership of Jobs sought to keep products simple and easy to use. Only in Jobs’s absence did the company produce complicated and clunky devices. Jobs and Markkula were also adamant that the Apple user experience must start with packaging. Upon joining Apple, Markkula stressed the importance of first impressions, and made sure the product’s design and packaging generated excitement from users — even before they’d switched the machine on.

Ive wholeheartedly endorsed this concept, later setting up Apple’s iPod Unboxing Room, a space where he and other designers would sit with hundreds of different types of boxes, figuring out which unboxing experience customers would enjoy the most.

“One after another, the designer created and tested an endless series of arrows, colours and tapes for a tiny tab designed to show the consumer where to pull back the invisible, full-bleed sticker adhered to the top of the clear iPod box,” Adam Lashinsky detailed in his book, Inside Apple. “Getting it just right was this particular designer’s obsession.”

Curiously, Apple’s ‘Designed in California’ declaration, which prominently features on both Apple packaging and hardware, isn’t entirely true. All Apple products, from the Apple II to the present-day iPhone, are heavily influenced by German industrial design. Jobs was a huge admirer of the early-20th-century Bauhuas movement, which among its many traits features beautiful soft curves and clean, minimalist typography. To this day, both are synonymous with Apple.

In the early 1980s, Jobs awarded a design contract to German Hartmut Esslinger, also a Bauhaus fan. Although Esslinger proposed Apple have a “California global” look, inspired by “Hollywood and music, a bit of rebellion, and natural sex appeal”, his Bauhaus influence remained prominent. It’s also no accident that all of Jobs’ cars were German: Volkswagen, Porsche, Mercedes.

Ive too was a huge fan of German industrial design, particularly the work of Dieter Rams, Braun’s chief designer officer whose “less but better” approach to device design helped make Braun a commercial sensation in the 1950s.

In truth, Apple borrowed from anything that aligned with its approach to clean design and paramount user experience. The flooring of the more than 500 Apple Stores globally is inspired by the Pietra Serena sandstone sidewalks of Florence, Italy; while the Genius Bars that provide everything shoppers need to know about any Apple product are influenced by the concierge desks at Four Seasons and Ritz-Carlton hotels. Inspiration can and should come from anywhere.

Achieve the unachievable

One of Jobs’s most notable traits was his tendency to stretch the truth when convincing engineers that a particular task was possible — when more often than not, it scientifically wasn’t. Apple employees called this the “reality distortion field”. The term is taken from an episode of Star Trek in which aliens create their own world through mental force. “In his presence, reality is malleable,” software engineer Bud Tribble, who worked on the original Mac, once said. “He can convince anyone of practically anything.”

Jobs’s flexibility with the truth annoyed many Apple employees. Yet it frequently inspired staff to accomplish tasks that were widely considered unattainable, recalled Herzfeld. This was especially evident with hardware design, where the casing was designed first. Engineers would then have to fit the necessary components into this casing. Most other manufacturers do the reverse, starting with the building of components then constructing a shell to protect them.

“You realise it can’t be true,” Wozniak once recalled. “But he somehow makes it true.”

The confidence of Jobs in both his and Apple’s abilities went beyond convincing staff to achieve the seemingly impossible. He would frequently disregard tried and tested ways of doing things. One such discipline was market research. “Customers don’t know what they want until we give them something,” he once said. “Did Alexander Graham Bell do any market research before he invented the telephone?”

Even the notion Think Different is grammatically incorrect: it should be ‘think differently’. In English, an adverb follows a verb, not an adjective. Instead, Jobs treated the word ‘different’ as a noun, as in ‘think big’, or ‘think beauty’. Only Jobs could get away with this.

Lasting legacy

When Jobs died in 2011, employees, investors and customers alike feared that the company would lose its way. They couldn’t have been more wrong. Under Cook’s guidance and, until 2019, with Ive’s designs, Apple has continued to thrive, and is still by some way the largest company in the world. While Cook is no Jobs when it comes to giving rousing product launches, he and his colleagues and partners continue to share their journeys and experiences, encouraging Apple users to make a difference in the world.

“Be the pebble in the pond that creates the ripple for change,” asserts Cook. “You can change the world.”

We at CP5 are passionate about telling deep and insightful business stories. Drawing from careers that saw us work for some of media’s most respected names, we help today’s leading brands to create bespoke reader-stories that frame their projects and achievement as epic journeys in their own right. Whether it’s through feature stories, special reports and whitepapers; or via video, training or live curated events, our solutions are tailored to your company’s needs — allowing you to focus on changing the world.

To learn more about how we can help tell your story, talk to us today.

This feature was written largely based on information drawn from the following books, supplemented by various online articles and web sources:

- Apple, Inc.: Strategic Analysis of a Global Powerhouse by Wendy Keller, Patricia Perrier, Bridgett Larkin, and Brad Burian

- Apple Inc. (Corporations That Changed the World) by Jason O’Grady

- Inside Apple: How America’s Most Admired—and Secretive—Company Really Works by Adam Lashinsky

- After Steve: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul by Tripp Mickle

- Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

- Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart into a Visionary Leader by Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli

- Steve Jobs: The Man Who Thought Different by Karen Blumenthal

- I, Steve: Steve Jobs in His Own Words by George Beahm